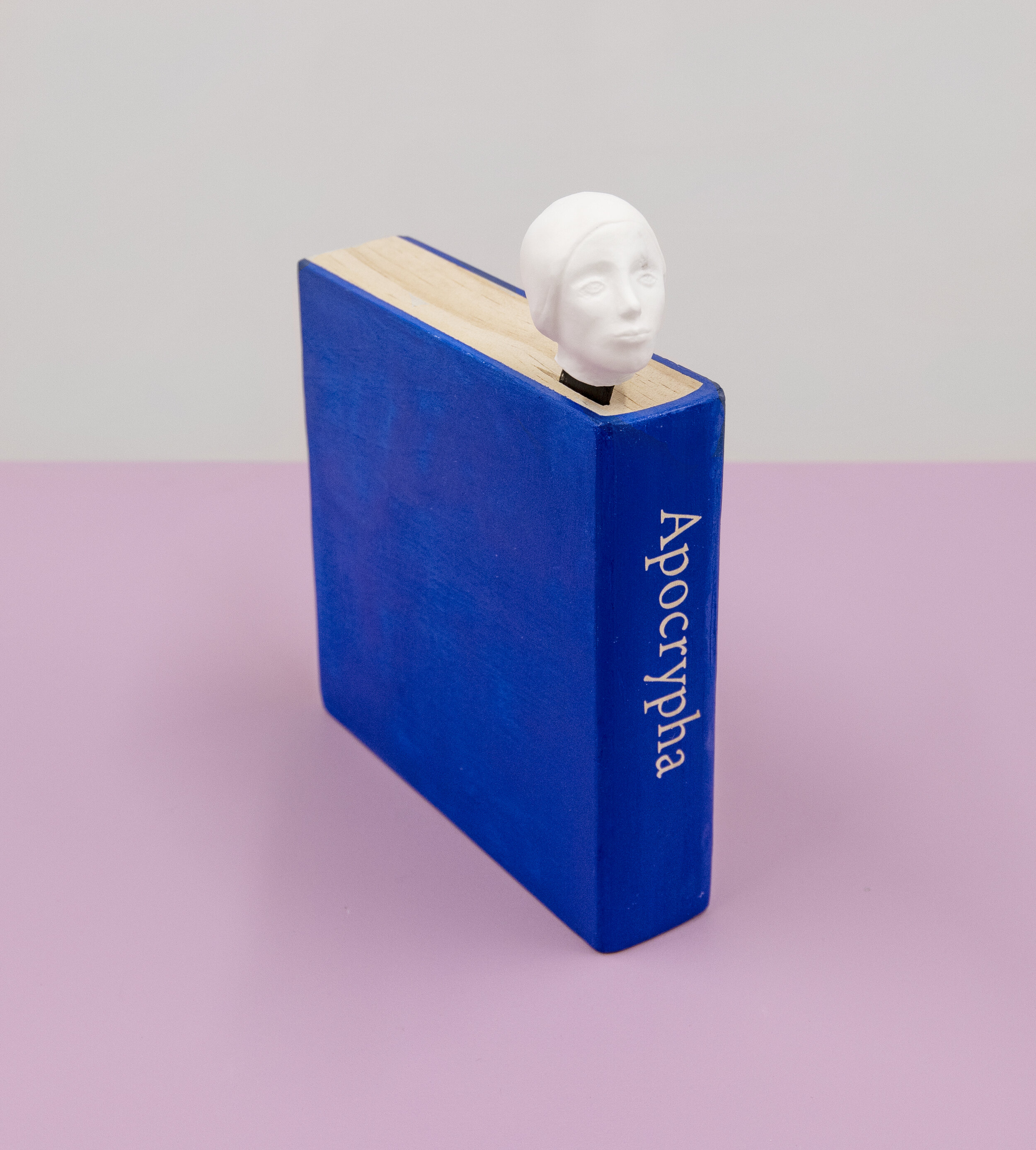

Dabin Ahn, Apocrypha, installation view. Curated by Stephanie Cristello, Chicago Manual Style 2020.

CHICAGO, IL—Chicago Manual Style is pleased to present the first solo exhibition, entitled Apocrypha, of artist Dabin Ahn (b. 1988, South Korea). The experience of viewing Ahn’s work often references the material history of the original object it imitates through various means of perceptual deceit—for example, two-part liquid plastic replicating the properties of porcelain, or carved Styrofoam and acrylic made to appear as thrown and glazed ceramic. These signals of artifice point toward Ahn’s interests in the inevitable material attraction held by items of luxury in ways that question authorship, technique, and the very substance of the aesthetic and utilitarian things that surround us. The exhibition examines certain symbols and myths throughout the history of primarily Western painting and sculpture as a means of inserting the artist’s own objects of desire within this canon through two bodies of recent work.

The first and central signifier of the exhibition is the Royal Copenhagen emblemata, founded for the famed porcelain house in the eighteenth century, which pictures the insignia of a crown above three waves, meant to symbolize the three major bodies of water the company’s origin country of Denmark. Ahn’s ornamental investigation into the markings upon the backs of collectible plates, made by centuries of artisans, delves into a larger experiment of authenticity—including a range of works from plates, to china, to figurines that present the logo in its true arrangement, as well as freer expressions and abstractions of its form.

In conversation with this principal motif are works that contain allusions to the lore surrounding the origins of the Nike check logo, rumored to have been conceived in reference to the iconic missing wing of the goddess statue of Samothrace c. 190 BC. Discovered by a French amateur archeologist in the mid-nineteenth century, the eighteen-foot sculpture of Nike—wet and wind-blown, drapery clinging to her body, as a frontispiece of a ship—was originally excavated in three parts: the base, torso, legs, and left wing.[1] The right wing, which was never found, exists as an addition to the sculpture, a perfectly symmetrical plaster appendage, which can still be seen today at the Louvre. Through a series works that reference the replica of the wing, alongside images of both the goddess and the logo appearing as a stamp upon plates similar to the Royal Copenhagen works, the phantom wing of Nike becomes an exercise in exploring how form is given to absence.

The exhibition as a whole utilizes the lens of branding to investigate the material history of objects. In both bodies of work, the aesthetic intersection of the color blue (used as both a motif and subject) unfolds across Ahn’s material forgeries. As the title of the show, Apochrypha, suggests—derived from the Greek word meaning ‘hidden’ or ‘secret’ and used to describe works of doubtful authorship—Ahn takes two very concrete symbols and transforms them into a tale of speculative origin. This aim, reflected throughout each of the works within the exhibition, is further explored by the scenography of the show in the method of display, with many of the works resting upon museum pedestals that have been painted to appear as commercial-grade Styrofoam. Here, the “Pink Panther” brand of construction material takes on new meaning; as in Ahn’s work, where elements of comedy and mystery are intertwined, the allusion to the character serves as a critique of our current art world, where the archetype of the jewel thief is no longer relevant.

Within the context of collectible artifacts, be they art or décor, Ahn questions value through various material investigations that lead to one end: the capital of the image.

—Stephanie Cristello

For images and press inquiries: info@chicagomanual.style

[1] French diplomat and amateur archaeologist Charles Champoiseau unearthed Winged Victory, also known as the Nike of Samothrace, in April of 1863.